Welcome to the working week. Here's what we're looking at today: Russia looks to China for military aid, Europe replaces pricey gas with cheap coal, high metals prices trouble American green industry, Finland opens new nuclear power plant, ISO-New England prices down from January for now.

Headlines

Russia's invasion to have 'enormous impact' on world food supplies. (FT)

Russia asks China for military assistance in its invasion of Ukraine. (FT)

California's ambitious high-speed rail at a crossroads. (NYT)

China locks down all of tech hub Shenzhen as covid cases jump. (BBG)

Real-estate binge pushes Canadian household debt to new record. (BBG)

Fossil

Europe ramps up coal burning with natural gas out of favor. (BBG)

China to expand coal use as it prioritizes energy security. (OP)

$4 gasoline could lead to demand destruction in the US. (OP)

Libyan oil under threat as militias amass in Tripoli. (OP)

Chairman Glick says FERC permitting does not limit more LNG exports to Europe. (SPG)

Renewables

H2 Green plans renewable hydrogen network in Scottish highlands. (SPG)

'Son of Build Back Better.' Energy CEOs eye renewables' future. (E&E)

Rising metals prices threaten US green energy push. (E&E)

Octopus Renewables signs deal to increase wind portfolio. (Reuters)

Californian port gets $10.5 million to prepare for floating wind activities. (OWB)

Nuclear

Finland opens nuclear power plant amid concerns of European energy war. (Guardian)

Early site work to begin for new Canadian SMR. (WNN)

US program supports Ghana nuclear progress. (WNN)

Germany disappoints again, Belgium flirts with reason. (ANS)

Grossi returns from talks with Ukrainian and Russian foreign ministers in Turkey. (ANS)

Grid

Power generation faces challenge of both transmission and transition. (Reuters)

ISO-NE Tracker: February power, gas prices decline from colder January peaks. (SPG)

How electricity grid reforms gulped up N831 billion in 6 years. (DT)

AEP completes transmission upgrade project in West Virginia. (PG)

Aged electric grid threatens Palo Alto's climate change goals. (PAO)

"The king stay the king."

It's been years since I've watched The Wire, but seeing reports of coal's resurrection in Europe reminded me of this scene, where D'Angelo teaches Wallace and Bodie the rules of chess. Wallace, at one point, asks what it takes to become a king.

"It ain't like that," D'Angelo says. "See, the king stay the king, a'ight? Everything stay who he is." The rules of chess serve as a metaphor for the structure of their drug empire. As it goes for the kingpin, so it goes for baseload energy: the king stay the king. And that king is coal.

Coal's hard to get rid of because it's abundant and cheap. It's also been around as an energy source for centuries. The hope for the "energy transition" was that a combination of natural gas supplemented by renewables (though it was sold to the public the other way around) would cut CO2 heavy coal out of the mix. Things looked optimistic.

But reality makes for a bitter teacher. The plan worked so long as gas stayed cheap. When a post-pandemic demand rebound hit during a wind drought just when gas inventories sat troublingly low going into winter, the transition shifted into reverse. The reason? Gas prices got too high to pair well with wind and solar.

Last month, Ember released a report that revealed that renewables succeeded in displacing their former ally natural gas in favor of far dirtier coal.

But now the dynamic has accelerated because of the Ukraine war. Suddenly, Europe finds itself scrambling to punish Russia That dependency rested on Gazprom, the Russian natural gas giant, in an already tight gas market. Coal leapt the preference queue as an offramp despite Russia's presence as a larger contributor to Europe's coal imports. Here's what coal use looks like YOY in Europe right now, according to Bloomberg.

And it's not just Europe. China, once the darling of Green New Dealers like Naomi Klein, has decided to recommit itself to coal. According to Oilprice.com, "China plans to increase its crude oil, natural gas, and coal production, boost reserves of energy commodities, and keep stable imports to ensure its energy security amid skyrocketing commodities prices, the top Chinese economic planner said last week."

This ought to inspire deep reflection in climate hawks. If the "meteor crashing into earth" crisis they built their policy around can be so easily demoted in priority, that's a problem for them in the long run. If their technologies of choice--wind and solar--helped rescue the dirtiest energy source we have next to wood instead of greening the world, then that's an even bigger problem.

But the difficulty here goes deeper than all this. Earlier this month, I interviewed John Constable of the Mont Pelerin Society about the fiction of the Industrial Revolution. Constable, after careful inspection of the historical record, noticed that the phrase "industrial revolution" only came about decades after it was said to have occurred.

How could it be that those living through the so-called revolution didn't recognize it as such? He found this curious. So he looked closer and found that the coal economy does of course ramp up in the early 19th century, but that that was a crest in a longer rising tide of energy density.

In other words, the Industrial Revolution (with capitals as we've come to think of it) was hardly like a swift revolution at all, but more like a long gathering of thermoeconomic ability. Thinking we can force an energy transition the way we created the Industrial Revolution misunderstands the timeline of the events and gives us unworkable expectations. These things happen in decades and centuries, not months and years.

And that's why coal stay the king.

Crom's Blessing

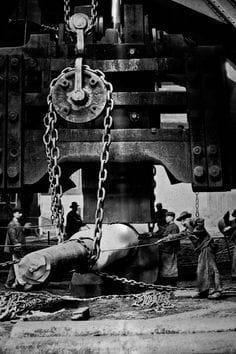

Forging press designed by Alfred Krupp, 1861.